The National Archives UK has been working with University of Warwick and five UK archive partners to develop a statistical model which quantifies digital preservation risk. This decision support tool allows digital archivists to compare and prioritise preservation policies and offers a way of understanding digital preservation as a complex network of interdependent risks rather than a prescriptive list of practices and policies to keep their collection preserved. For more information on the project see our webpage.

Modelling digital preservation risks

At the beginning of this statistical research project, we began by identifying what outcomes are most important to a digital archive when considering digital preservation. Three concepts stood out – the ability to render the object in a sufficiently useful way, having the full knowledge of the material content, provenance and conditions of use, and trust. All project partners felt passionately about trust and we spent a long time discussing its different aspects and importance to our work. After all, what is the point of making copies, maintaining optimal storage conditions, learning how to emulate software etc. if prospective users don’t trust us?

A trusted digital repository is one whose mission is to provide reliable, long-term access to managed digital resources to its designated community, now and in the future. This was the definition of trust we had for our model which I think summarises this complex concept well, highlighting how it needs to come from the very core of the custodial institution. Being open and transparent is key, especially about the provenance of the records, why we have them (and by implication why not others) and what steps we’ve taken to ensure they’ve been preserved.

Definition sorted. Next question: what data do we have to measure this?

Being a statistical project, we needed data. If trust was to be a variable in our network, we’d have to agree on a way to measure it. Some ideas were floated about looking at whether an archive had formal accreditation or certification, but measuring trust by these actions alone would misrepresent what we were trying to capture. Other suggestions were to look at user surveys and complaints, but this posed the heavy bias that these people would already be users and not consider other communities who may not trust the archive enough to make use of its services.

It was at this point we had to take a step back and really think about how trust links to digital preservation. We decided that trust could be broken down into two elements – trust in the record and trust in the custodians. Trust in the record is something that more easily lends itself to be quantified, and our model today considers the risk of loss of integrity which can be mitigated against by having secure systems, fixity policies and good information management. Through this we are mimicking what trusted digital repository certifications are there to achieve – assessing whether the preservation policies are as a sufficient standard to keep the records safe. Trust in the organisation is the difficult part, and something that an individual archivist has a lot less influence over. Therefore trust, in this latter form, was removed from the statistical model.

A separate model for trust

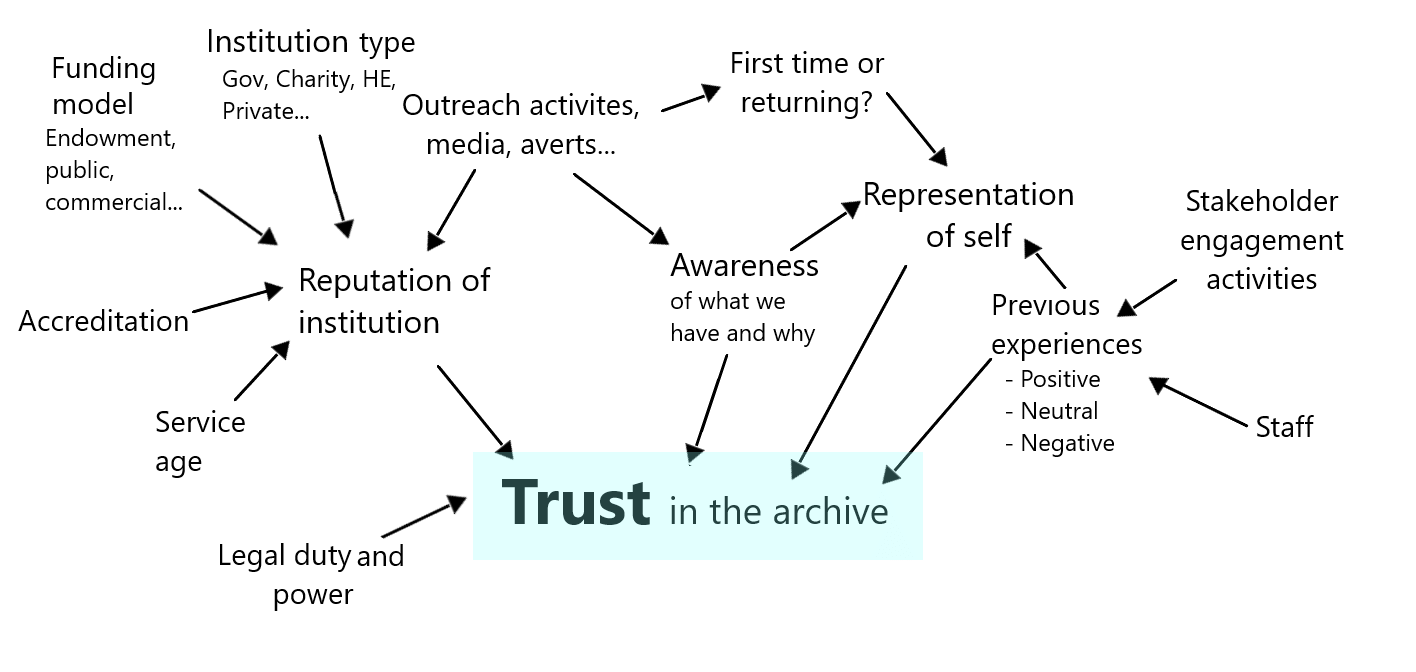

However we still believe that trust in the digital archive is something that we must not lose sight of, so those of us at The National Archives have attempted to create our own risk network for trust and all the factors that affect it. The arrows in the image loosely represent the direction of the relationships between the variables, for example service age impacts the reputation of the institution, which then directly impacts the perceived trust in the archive.

Trust is a personal belief and one of the main differences between this network and the digital preservation risk model is that nearly all of the aspects here are subjective – something we are working hard to remove from our quantitative model. Compared to the statistical model, it is also not clear cut how these variables impact trust, only that they do. And there are some variables here that an archive cannot change, for instance its service age or institution type.

There are several different stakeholder groups from which trust is essential. The user of the archive is the obvious one, but gaining trust from depositors, funders, and other archives are important considerations too and in some cases critical to survival of the collection. All these need to be considered in a balanced way to ensure an archive can provide its service effectively into the future.

Another interesting dynamic is the institution’s legal responsibility. Under the UK Public Records Act 1958, The National Archives has a duty to take all practicable steps for the preservation of records in our care, so if a record is lost there can be legal consequences to compel the institution to act. Having a recognised legal duty can provide reassurance to depositors and users but could also be negative if you are found to be disobeying or if you fail an audit.

So, what next?

Although we are not taking this any further for now, it has the potential to form a substantive social research project to increase our understanding of what really drives trust in digital materials and their custodians. If you think there is traction for this kind of research or are aware of some already, please let us know in the comments or email [email protected].

Note: This network had been created with a digital archive in mind but all of these concepts are applicable to analogue archives too. However, for institutions with both analogue and digital holdings it may be helpful to assess these separately, particularly accreditation and outreach activities, as performance against these for analogue may offer no change in trust of the digital records and vice versa.