Flashback is a proof of concept project run by the British Library’s Digital Preservation Team. The project is examining specific emulation and migration solutions as methods for preserving digital content held in the Library’s stock on 3.5” and 5.25” disks and on CD and DVDs. These could be software items but are mainly supplements to print publications, most commonly with magazines and reference books.

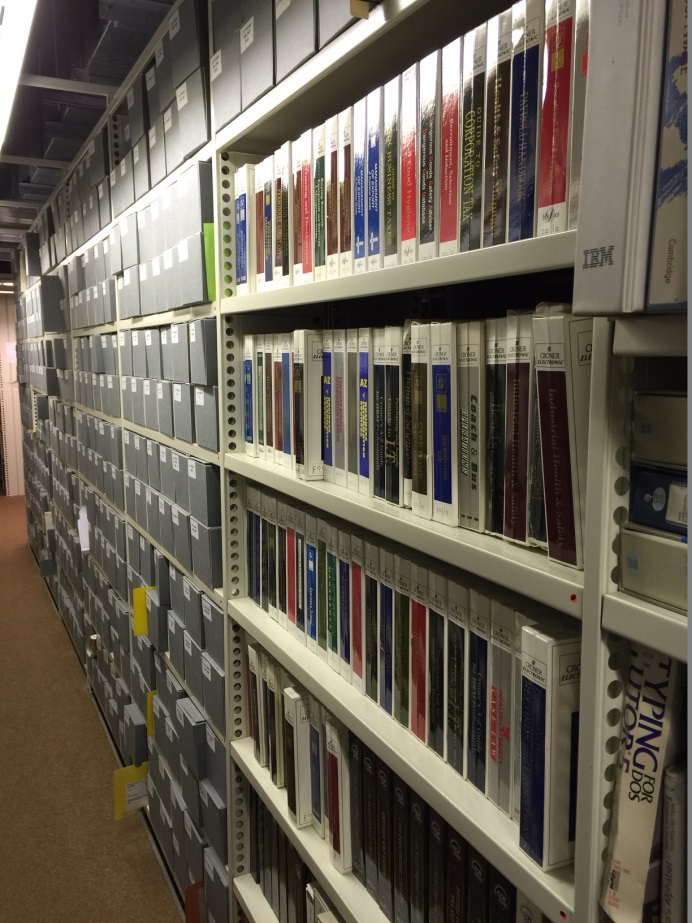

Phase 1 of the Flashback project ran from the Summer of 2015 to Spring 2016. During this time, a lab of legacy machines was established and an initial sample of 50 items from the Library’s collection, ranging from 5.25” Floppy Disks from the 1980’s to DVDs from the early 2000’s, was tested on both legacy machines in the lab and a self-hosted instance of the Freiburg Emulation as a Service platform. Approaches to the long terms preservation and access of disk images were also investigated.

Phase 2 began in summer 2016, with plans to upscale not just in terms of the actual number of content items imaged and tested but also the range of collections nominated. By the end of phase 2, nearly 700 items have been imaged (which equates too almost 900 floppy disks and CD-ROMs). It was decided in Phase 2 that, with curatorial input, specific collections would be targeted from Library stock. These included:

- CD-ROMs which are contained in the Library Social Sciences Reading Rooms (1994-2009)

- A collection of disks and CD-ROMs which came with two magazines (1987-1998)

- Croner’s Electronic material on both disk and CD-ROM (1995-1999)

- Selection of disks which had accompanied a variety of books (1986-1995)

- A small bespoke collection of material nominated by curatorial staff across the Library (1998)

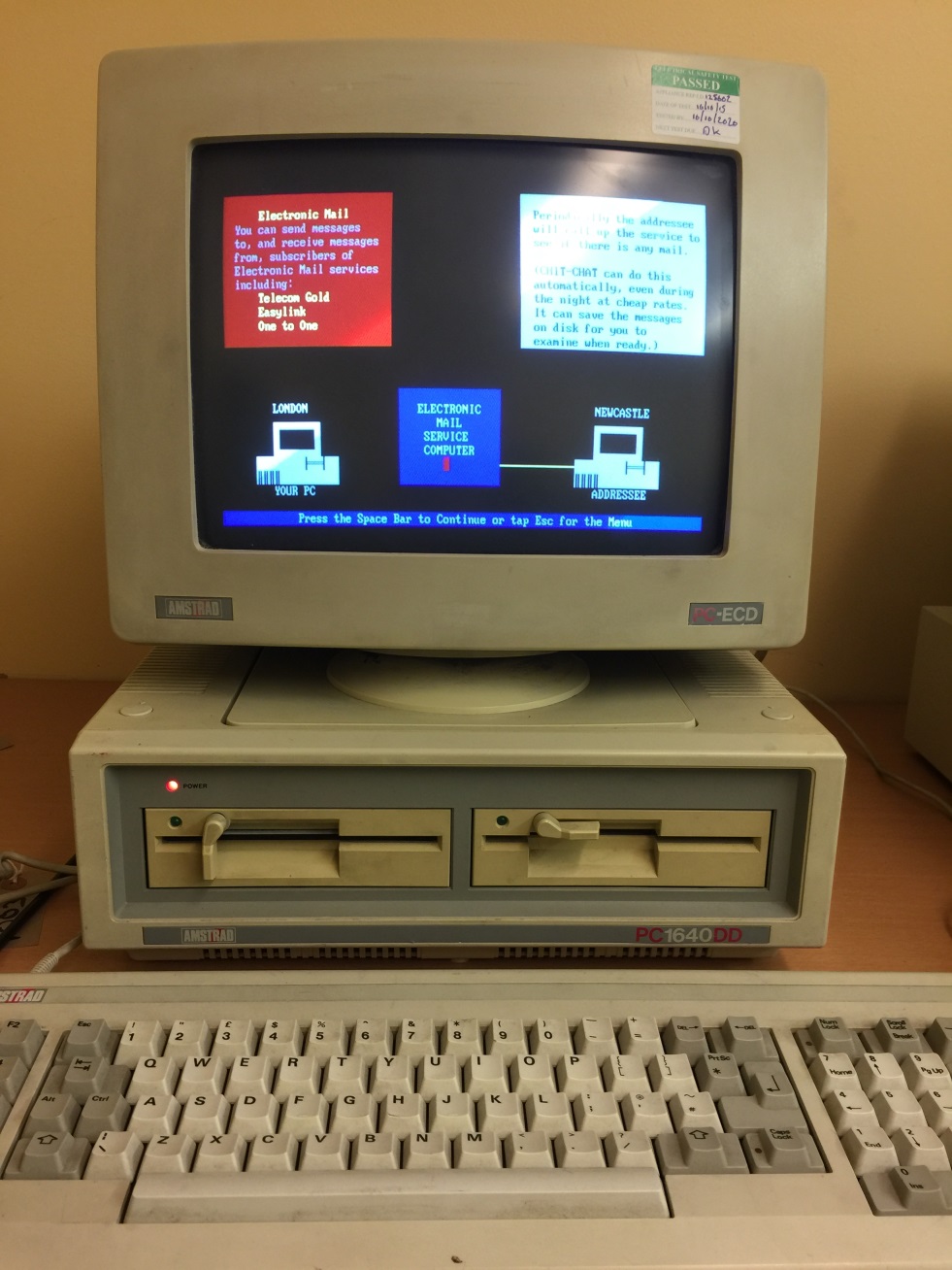

Since the conclusion of phase 1, growing awareness of the Team’s work has meant several new (old) machines have been donated. This has made the accessing and testing of some material (particularly DOS and Windows 95/98 items) in their original environments and hardware a lot more straightforward . The Lab is still growing (and new items are always considered!) and has become a great feature for engaging internal and external visitors with the message of digital preservation. The acquisition and promotion of the Lab and the Flashback project has also led to work being referred to the team from other Library Staff. This could be extracting disk content where they had content they couldn’t access or, more anecdotally, had old items or information lurking on disks in the bottom of drawers which they wished to rediscover.

You will recall from Edith’s previous blogpost that many of the old machines had their quirks and periods of misbehaving. Whether it has been spending longer periods working with them or just getting used to their quirks, some have started to feel more stable, mainly because you start to accommodate the way they (mis)behave. But they do continue to remind you that hard drives used to be very small and it isn’t long before a spring clean is needed (if they have a hard drive at all)!

Whilst for now these machines are continuing to survive (and as a colleague who unsuccessfully attempted to repair a broken 3” disk drive and ended up covered in black goo will no doubt remind me) they won’t last forever. They still, though, provide a useful testing ground and benchmark for exploring what the content looked like in its original environment and how it performed.

Creating a disk or CD image followed the workflow created in Phase 1 with some tweaks added to the script we used. The automated creation of statistics that we had created on a manual basis in Phase 1, such as extraction timings and the file formats contained in each image are now produced alongside the technical information, checksums and metadata previously captured.

With almost 98% of the content having a useable image, it might be easy to assume there isn’t a huge risk to the content through media deterioration. This, though, may not be the case as we found examples where images extracted from certain items run successfully in emulation but won’t run at all on the original hardware. It is more likely that the tools available to extract content (especially from the 5.25” disks) are very efficient at what they do and that we have become a lot more proficient in using them.

Whilst automating some of the process has allowed us to generate some information (on object content for example), recording the behaviours and structures of an item is more labour intensive. Doing this for all 900 items would be impractical so decisions were made at the collection level on representative and random sampling depending on the collection.

Disks from a single collection will feature quite similar or identical content but others such as magazine or book disks can contain large quantities of heterogeneous content each with the possibility of containing their own hardware and software dependencies. The use of emulators has allowed us to view the content on a modern machine but often a bit of installation research is required simply to get the items up and running.

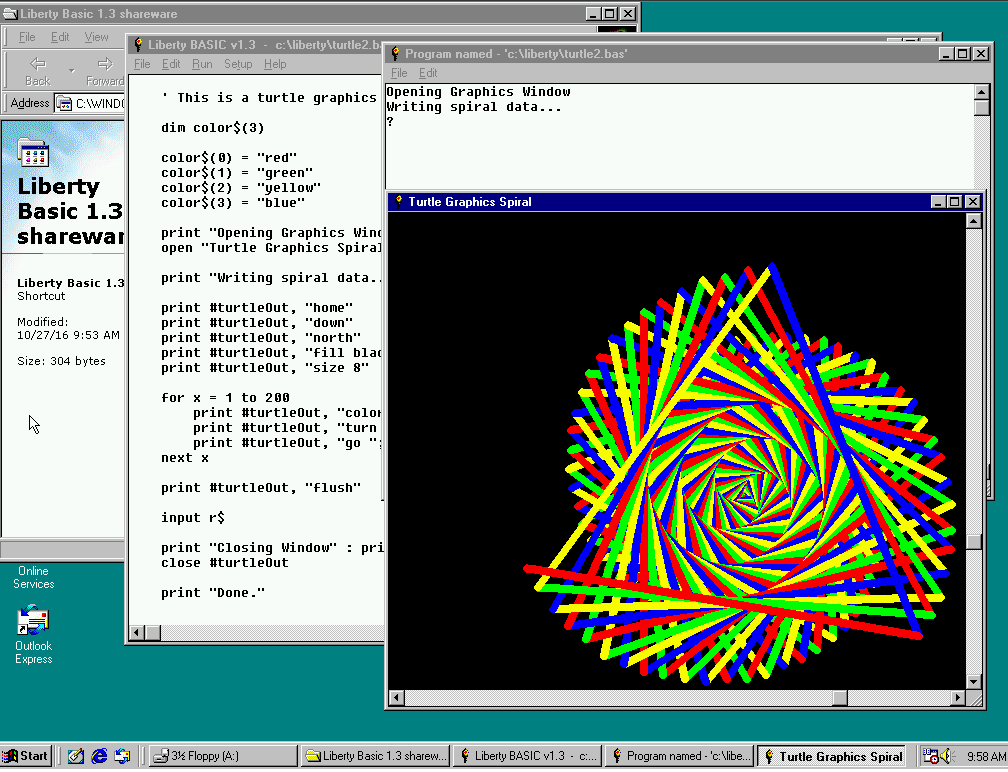

As with Phase 1, we have continued to work with the bwFLA Emulation as a Service product for emulating the images and again this was the main approach taken for testing and investigating the provision of future access to the content. Something to bear in mind when thinking about the migration versus emulation argument is preserving the experience of using and installing the software. Is this as important an aspect to recreate as accessing the content is itself for current and future researchers? The provision of an “authentic” experience for the user of the software is something that does need to be considered in decisions about access.

In terms of problems with the experiments, we had several minor issues around the emulators themselves rather than the service itself (for example, in our case the Qemu – DOS environment had German text and keyboard layout as a default) which were easily fixed with a small amount of coding changes. Playback on some emulators was also a problem with certain objects. DOSBox offered a more faithful recreation of a disk image with many games made unplayable or graphical representations inaccurate on Qemu emulators when compared to their playback on legacy hardware.

There is still a lot of work to do in providing access to the content, as well as navigating the access and licensing issues of making the content available to users which we have progressed in Phase 2. Something we will hopefully talk about more in a future blogpost. As the proof of concept draws to an end the exciting prospect of the workflow becoming business as usual becomes closer to a reality.

For more information on the project, please read our recently published article in Alexandria magazine http://ala.sagepub.com/content/early/2016/10/17/0955749016669775.full.pdf+html or get in touch at [email protected].