Earlier this week the National Archives of the Netherlands (NANeth) published a report on preferred file formats. It gives an overview of NANeth’s ‘preferred’ and ‘acceptable’ formats for 9 content categories, and also explains the reasoning behind the selected formats. Even though in Dutch language only, the report is well worth a look. However, I found a few of the choices a little surprising, especially the ‘spreadsheet’ category for which it lists the following ‘preferred’ and ‘acceptable’ formats:

| Preferred | Acceptable |

|---|---|

| ODS, CSV, PDF/A | XLS, XLSX |

The report gives the following explanation on the ‘preferred’ formats (translated from Dutch):

- ODS – ODS is part of the OpenDocument standard (ODF, NEN-ISO/IEC 26300:2007), which is listed as the standard for office documents on the ‘act or explain’ list of ‘Forum Standaardisatie’1

- CSV – for the storage of non-interactive information in cells, a comma-delimited (.csv) text file can be used instead of a spreadsheet

- PDF/A – PDF/A is a widely used open standard and a NEN/ISO standard (ISO:19005). PDF/A-1 and PDF/A-2 are part of the ‘act or explain’ list of ‘Forum Standaardisatie’. Note: some (interactive) functionality will not be available after conversion to PDF/A. If this functionality is deemed essential, this will be a reason for not choosing PDF/A

In the remainder of this blog post I will pinpoint some problems of the choice of PDF/A and its justification.

Demo spreadsheet

To illustrate my arguments, I created a simple demo spreadsheet in xlsx format (created in Microsoft Excel 2010). It contains two columns:

- Column A: random number between 0 and 100 (as static values)

- Column B: formula that takes the value from Column A and adds its square root:

=A2 + SQRT(A2)

Displayed precision not equal to stored precision

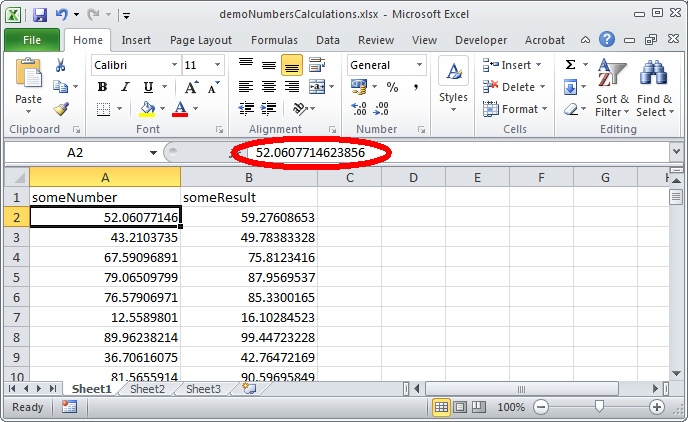

Without applying any special formatting, this is what the spreadsheet looks like in MS Excel 2010:

The first thing of interest here is that the displayed values in the cells are different from those that are actually stored! For example, the value that is shown in cell A2 is:

52.06077146 Note that 8 decimal places are shown. But by looking at the formula bar you can see a different value:

52.0607714623856 which contains 13 decimal places. Since Excel internally stores numbers at a precision of 15 significant figures, only the latter corresponds to the actual (stored) value.

Loss of precision after exporting to PDF/A

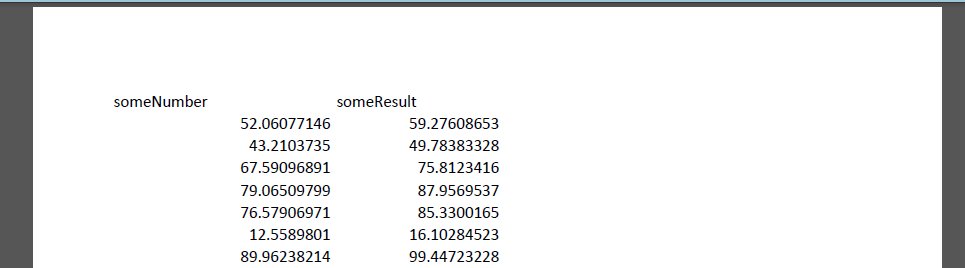

I exported the spreadsheet to PDF/A-1a using Acrobat PDFMaker. The result can be found here. Below is what the PDF looks like when opened in Adobe Acrobat:

So, the PDF only contains the values at Excel’s displayed precision (in this case typically 9-10 significant figures), and the remaining precision got lost in the conversion.

In addition, unlike the source spreadsheet, the PDF only contains static numbers. This means that information about the relation between the values in Columns A and B (i.e. the formula) is completely lost.

Loss of precision after exporting to CSV

Interestingly, exporting to a comma-delimited text file resulted in the same loss of precision! See the exported CSV file here. For brevity I won’t go into any further detail on CSV, but it’s important to be aware that this issue exists.

Effects of cell formatting

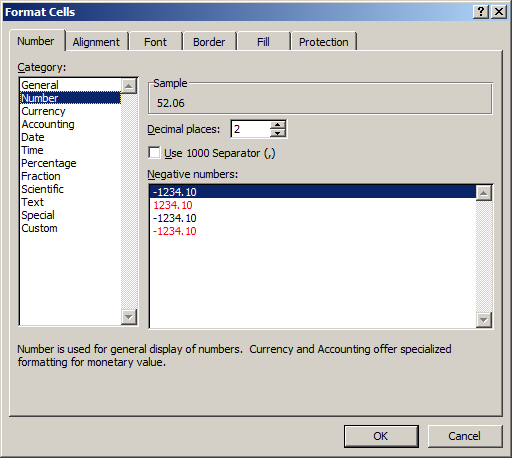

A possible way around the rounding issue would be to use Excel’s Format Cells dialog, which allows one to set a fixed number of decimal places to be used for display:

This is also less than ideal, if only for the reason that a fixed value will result in the display of non-significant figures. For example, applying a setting of 14 decimal places to the value in cell A1 results in:

52.06077146238560which is different from the stored value:

52.0607714623856 Moreover, this approach gets extremely cumbersome for spreadsheets that contain numbers at different precisions (e.g. it is pretty common to have one column with integer values, and another one with floating-point numbers).

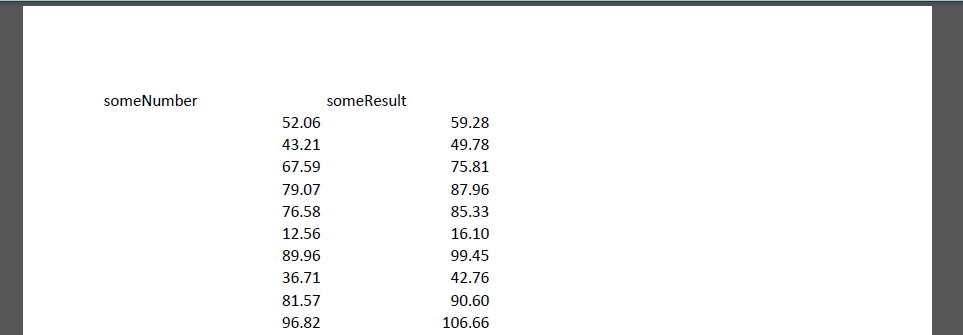

In practice, Excel’s number formatting is often used to reduce the number of displayed digits (e.g. to make the columns more visually pleasing, or to avoid messy output when printing). Here’s a version of the spreadsheet where I adjusted the formatting to display two decimal places only, and here is the resulting PDF. It looks like this:

So in this case even more information is lost!

Interactive or dynamic?

The preferred formats document does acknowledge that PDF/A may not always be suited for spreadsheets, using the following statement (in Dutch):

Let wel: bepaalde (interactieve) functionaliteit zal na omzetting naar PDF/A formaat niet meer beschikbaar zijn. Als deze functionaliteit als essentieel wordt beschouwd, is dit een reden om niet voor PDF/A te kiezen

Which translates in English as:

Note: some (interactive) functionality will not be available after conversion to PDF/A. If this functionality is deemed essential, this will be a reason for not choosing PDF/A

This statement is problematic for various reasons. First, whether functionality is deemed ‘essential’ largely depends on the context and intended user base. By stressing the interactive aspect, the authors imply (perhaps unintentionally?) that any spreadsheets that do not take any interaction with a user can be safely converted to PDF/A. But what does ‘interactive’ mean in this context? Taking my earlier sample spreadsheet as an example: a user may ‘interact’ with that spreadsheet by changing the values in Column A, after which all values in Column B are recalculated. Does that make it interactive? If yes, applying the ‘interactivity’ criterion like this would cover any spreadsheet for which the value in any cell is dependent on one or more values in other cells. This applies to most spreadsheets, apart from those that only contain static data. But in that case a distinction between ‘static’ and ‘dynamic’ spreadsheets might be more useful2.

Reading PDF/A spreadsheets

Finally, I’m quite puzzled how a PDF/A representation of a spreadsheet is meant to be read. Who are the intended users? What is the target software? What is the context? Sure enough a PDF may be sufficient for on-screen viewing, but what if a (future) user wants to recover the original row and column values? Excel is not capable of this (in fact it cannot even import a PDF at all)? What if someone wants to use the data for some actual calculations? Data extraction from PDF is notoriously difficult (hence the phrase "pdf is where data goes to die"), which is mainly due to the lack of structure of the format3.

Concluding remarks

The above observations only scrape the surface of the perils of using PDF for spreadsheet data. To be clear: there may be situations where PDF/A is a good (and possibly even the best) choice. For example, spreadsheets are often used for printable forms, and having these as a PDF/A representation may be perfectly fine4. Nevertheless, NANeth’s recommendations on choosing between their ‘preferred formats’ appear to be suboptimal, because they do not take into account the purpose for which a spreadsheet was created, its content, its intended use and the intended (future) user(s). In particular, using ‘interactivity’ as the main criterion seems somewhat dangerous.

Data

The example files that are referred to in this blog post are all available here:

https://github.com/bitsgalore/spreadsheetsPDF

-

Forum Standaardisatie is a Dutch government body that promotes the use of open standards in the public sector.↩

-

On a related note, it is well known that (formulae in) spreadsheets often contain errors, and that these can have major implications (there are numerous examples on the Horror Stories section of the European Spreadsheet Risks Interest Group). Once converted to PDF/A, such errors are impossible to detect.↩

-

Andy Jackson once compared this to "reconstructing the cow from the burger"↩

-

Incidentally, spreadsheet forms can be highly interactive (e.g. by letting a user enter data by selecting a value from a drop-down list); this is again an indication that interactivity may not be a good criterion for deciding on PDF/A as a target format↩

March 17, 2021 @ 3:19 pm CET

As said on Twitter, what could be used for this purpose is the XMP[1] stream inside the PDF (which is mandatory with PDF/A). That would probably cause some data duplication, but at least it would be an obvious place where to search for interoperable content.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extensible_Metadata_Platform

March 17, 2021 @ 12:49 pm CET

I think this post belongs to the category “Preservation is not Interoperability”. Also the other side stands: interoperability is not preservation. Maybe surprisingly, this blog post is not citing the word “interoperability”, defined as the ability to exchange data and work with other software without restrictions[1], neither once. Serialization formats, for example markup/notation languages like XML, Json, or similars, allows for interoperability, without defining any visual aspect of the content. There are of course ways to store interoperable data in PDFs as redundant content, but having visual aspect based on interoperable data stored on the PDF itself it’s a topic I am not sure it’s covered by current PDF side standards. It there’s not an existing solution today, this could be truly a matter for a brand new standard.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interoperability

December 13, 2016 @ 9:10 am CET

First of all thanks to Johan for the interest taken in our preferred formats document and the feedback given in this blog. All of the arguments he makes about loss of precision are correct. That’s why we selected ODS as preferred and XLS, XLXS as accepted formats. Incidentally, the finding that CSV has precision issues was new to us and is certain to be part of our evaluation of our preferred formats document.

In this document we provide 2 lists: preferred and acceptable formats for different information categories (not only spreadsheets, but also including text documents, image files etc). A format is preferred when it’s an open standard as defined by the so called Forum Standaardisatie, a government agency dedicated to promoting usage of open standards in the Dutch central administration. Acceptable means it’s not (fully) open and documented but we already have the experience and the strategies in place to ensure longtime archiving.

The reason we included PDF/A – one of the formats included on the Forum Standaardisatie list – as one of our preferred formats is that in our experience spreadsheet are not only used for, say, complicated calculations but also to store plain text in a table format. In these kinds of spreadsheets, the individual cells do not interact with one another and what you see on your screen is all there is to it. In these cases – exclusively – we feel that PDF/A is an appropriate format for long term archiving. That’s what is meant with the phrase “Note: some (interactive) functionality will not be available after conversion to PDF/A. If this functionality is deemed essential, this will be a reason for not choosing PDF/A”. We call it interactive, Johan calls this dynamic, but I think we mean the same thing. To prevent misunderstandings we’ll probably explain in more detail what is meant by ‘interactive’ in future versions.

I had a chance yesterday to talk to Johan and we both concluded that spreadsheets are tricky. Feedback like his remarks are indeed appreciated and will be used to improve and update our preferred formats document in future versions.