The internet as archive, the Bass model in practice: which internet formats are disappearing?

Original author: Rein van ‘t Veer

Is it possible to predict which file formats are in danger of becoming obsolete? This project is part of the Dutch Digital Heritage Network (DDHN) Preservation Watch and Preferred Formats programme. This article is the second in a series on monitoring ageing file formats, you can read the first blog here. We will post the entire (translated) series on the OPF platform in the coming weeks.

In mid-2022, the Preservation Watch working group launched an open call for research on monitoring file formats and their life cycle. With the goal to investigate the predictability of ageing file formats. In October 2022, Rein van ‘t Veer started working on this project as an author and “data scientist”. In this article we look at the use of these methods in practice. We will be using the Common Crawl data collection as a webarchive, the experience will be used to analyse the files of Dutch archives in the following blogs. The Internet can increasingly be thought of as an archive, with the Internet Archive and Common Crawl as the main “archival institutions”.

Common Crawl

As a non-profit organisation, Common Crawl archived the past seven years of publicly accessible web data “scraped” from the internet. The main reason for using this dataset as a digital archive is that the organisation publishes usage statistics of file formats from the past five years in an easily accessible way; a series of benchmarks against which we can compare data from archives in the Netherlands and exercise the selected Bass and linear models.

Previously, large-scale web crawl data were really only available to large search indexes, but Common Crawl offers this data in petabytes of open web data, in billions of files and trillions of links. Fortunately, Common Crawl publishes all the statistics we want in aggregate form, so there was no need to wade through the sea of data. This results in a time series of 55 measurements for each of the 100 most common MIME types. We restrict ourselves to the media types that declined in use in recent years. By “decline” we mean here that past usage was measured to be higher than the last measured value.

To analyse the data, we used a script. The script is written in the Python programming language and has been released as open source code. Based on the 100 most common formats, we make counts of their popularity. Filtering the MIME types by decreasing usage, we are left with 26 expected and less expected file types. The 10 biggest decliners are:

- XHTML: a stricter version of HTML,

- HTML: the main web page format,

- Coldfusion: a now unpopular programming language for the web,

- ASP.Net: a programming language for web servers,

- RSS: a web format for publishing feeds of blog posts, articles or other news items,

- GIF: a file type for images,

- MPEG-4: a video file format,

- PowerPoint: the well-known presentation format,

- X-diff (missing a clear description on the web): a metadata format for differences in text files,

- Zlib: a standard and file format for data compression.

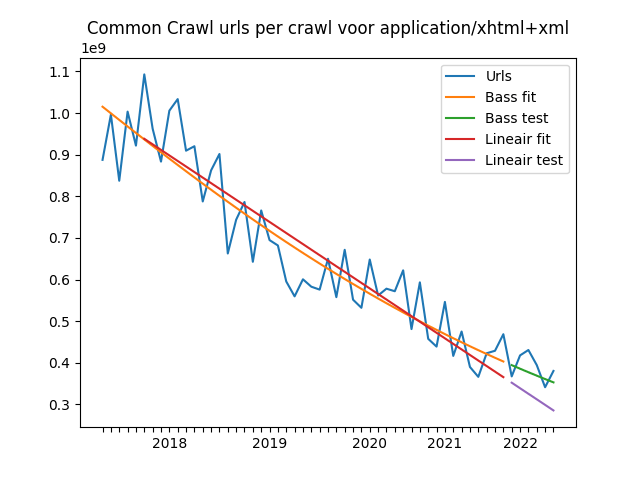

We will take a closer look at XHTML and GIF. By applying the Bass model to the data we will see to what extent the model makes sense to use as a predictive method, compared to a simple straight trend line. We will leave open the question of what would be a good “threshold value” for these formats to start converting them to a more modern format, to keep the length of this article somewhat contained.

HTML

XHTML has the largest decline by far. XHTML is a form of HTML, with stricter rules around correctness and validation. While XHTML still accounts for a respectable 12% share of web pages, the format is rapidly eroding in usage from the 15% share it had a year ago and a whopping 30% share of web pages 5 years ago. Van ‘t Veer’s suspicion was that XHTML is losing out to HTML5, the current web standard, although Tim Berners Lee, the inventor of the internet, had his doubts about it back in 2006.

GIF

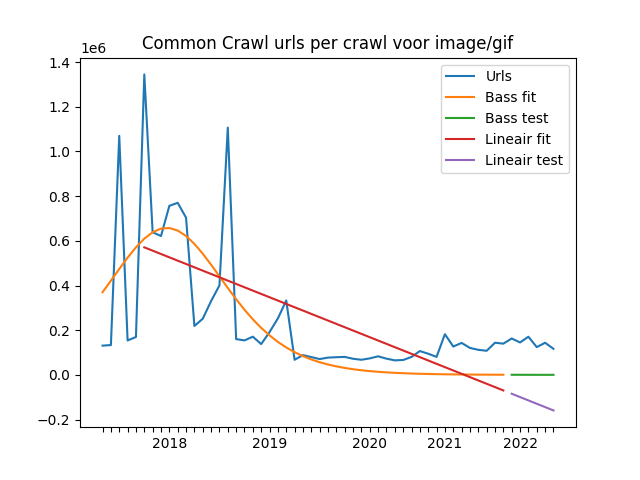

Other formats are experiencing much less dramatic declines. One notable one we want to highlight: the GIF format, which recently received attention in an online article on the history and uncertain future of the file type. GIF, specifically the GIF89a subtype, has long been the main format for displaying lightweight animations on a web page that looped automatically. Giphy is still a widely used platform to include these, but they are used more in chat applications than directly on web pages. Despite the graph showing a slight “bump” from May 2021 to May 2022, usage is declining in recent years.

Evaluation

For the two graphs of XHTML and GIF, there are a couple of striking things to report. None of the selected file formats have a logical 0-point in the data used: the formats themselves are much older than the statistics from Common Crawl. We cannot look at aggregated statistics before May 2017 on Common Crawl, and in general no further than their start date in 2014, while XHTML dates from 2000 and GIF going back until 1987. This means that we miss the vast majority of the years when these formats emerged on the web.

Nevertheless, the data from XHTML usage fits the Bass model quite well: it clearly does not need a zero date from 2000 to “fit” a nice curve. Unfortunately, this is true to a lesser extent for the GIF format. It is difficult to fit the strong peaks and valleys in the data into the model, and especially in the data on the right side of the graph, it is clear to see that the model underestimates how much GIF is still in use.

Nevertheless, both graphs do show that the Bass model does significantly better than the simpler linear trend line for these two selected file types. The greater flexibility of the Bass model means that the data can “fit” better in this model. This is true for all file formats in the Common Crawl data decline in use: the average error is generally lower for the Bass curve than for the linear curve:

| MIME type | Bass average error | Linear average error | Ratio Bass over linear |

| video/x-matroska | 192 | 6210 | 0.031 |

| text/asp | 34368 | 259793 | 0.13 |

| video/x-m4v | 1260 | 9720 | 0.13 |

| audio/midi | 2526 | 10759 | 0.23 |

| text/aspdotnet | 69091 | 287653 | 0.24 |

| audio/mp4 | 1187 | 2854 | 0.42 |

| text/x-coldfusion | 118534 | 285183 | 0.42 |

| application/xhtml+xml | 30815786 | 69746869 | 0.44 |

| application/x-dosexec | 4739 | 9884 | 0.48 |

| application/x-shockwave-flash | 9073 | 18741 | 0.48 |

| image/gif | 143626 | 265709 | 0.54 |

| image/bmp | 2731 | 4739 | 0.58 |

| application/vnd.ms-excel | 12010 | 19174 | 0.63 |

| application/rss+xml | 623531 | 79559 | 0.78 |

| application/javascript | 5232 | 5327 | 0.98 |

| image/vnd.microsoft.icon | 3915 | 3997 | 0.98 |

| application/x-debian-package | 1663 | 1673 | 0.99 |

| application/vnd.android.package-archive | 5135 | 4693 | 1.1 |

| application/text | 12480 | 9319 | 1.3 |

| text/x-vcalendar | 16333 | 12049 | 1.4 |

| application/vnd.ms-powerpoint | 16115 | 9448 | 1.7 |

| application/zlib | 7601 | 4305 | 1.8 |

| text/x-diff | 55492 | 10628 | 5.2 |

| text/html | 2351887901 | 338079635 | 7 |

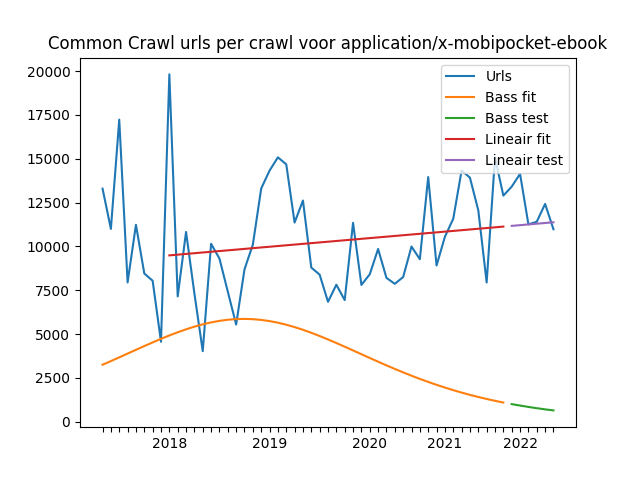

| application/x-mobipocket-ebook | 11454 | 1127 | 10 |

The results show that for 13 of the 26 web formats declining in use, the Bass model predicts significantly better on test data over the past six months in comparison to the simple linear trend line. In three cases the accuracy is almost the same, there are also as many as 8 web formats for which the Bass model does worse than a straight trend line, the most problematic being the Mobipocket ebook format. What happened there?

The interpretation here is that the irregularities in the numbers of URLs here are so large that the Bass model cannot find a good “fit” within the parameters of the model. From the linear trend line, it can also be seen that on average, this file format has a slightly increasing average, after the largest measured peak around 2018. Can we really speak of declining usage here? Based on this data, it cannot be said with certainty; Amazon bought Mobipocket in 2005, after which the company discontinued the format in 2011, three years before Common Crawl measurements had started at all. All these things will have contributed to the Bass model performing worse than the linear model in this regard.

Conclusion

We tested the Bass model and a linear trend line for their value as predictive models for the use of the main file formats on the internet, as measured by Common Crawl over the past five years. The average error of the Bass models and the linear models shows that in most cases the Bass model outperforms a simple straight trendline, but that this is certainly not true in all cases. If there are many irregularities in the measurements and it is questionable whether there is really declining usage, the Bass model seems to perform worse.

Does this mean that the Bass diffusion model is applicable for data from archives in the Netherlands? We will investigate this further over the course of the series using archive data from DDHN partners, with a greater time span than that of the Common Crawl. Overall, the Common Crawl data shows that we must continue to assess whether the model does better than a straight trendline over the period when decline in usage is seen, measured from the time of highest measured usage.

Event

Do you want to learn how to make predictions about the life cycle of file formats in an e-depot?

We will host an in-person workshop in Dutch where you get to work hands-on with your own data. Join us on 5 September, 2023, 13:00-16:00 in The Hague, The Netherlands. More information.

© 2022 CC-BY-SA-4.0 Rein van ‘t Veer/Network Digital Heritage.

Image: © 2022 CC-BY-SA-4.0 author, modified from https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:1614896.